Since the early days of cannabis prohibition in Minnesota, racism has been a driving force in increasing funding for enforcement and worsening the severity of punishment for those caught. While politicians today may claim that their support for drug enforcement is not racist in of itself, it does serve to support the continuation of policies that were originally developed to oppress and criminalize people of color and individuals experiencing poverty. John Ehrlichman, Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs under Nixon infamously explained that the original reason behind drug prohibition was to criminalize and lock up “hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin”. The point was and continues to be disrupting communities and arresting those seen by the political system as “undesirable”.

The original legislation passed to enforce the prohibition on cannabis in Minnesota was enacted in 1935, just two years prior to national criminalization. Chapter 321 banned the possession, production, and sale of “Cannabin” and punished those caught violating this law with a $1,000 fine and up to one year in prison (or over one year for subsequent offences). By the 1940’s, with the film “Reefer Madness” in Minnesota theaters, fields of cannabis (some of which was the low-THC plant commonly referred to as Hemp) were being burned by the acre.

While the Thirteenth amendment to the United States Constitution banned slavery, early enforcement of cannabis prohibition continued in the same vain by requiring those arrested for possession in Minneapolis to 90-days in a work house (which was considered liberal at the time). The Minneapolis Tribune reported on June 17, 1931 that the new city ordinance prohibited “marijuana, a Mexican drug.” Just a decade earlier, readers would have learned of the raid on those providing “a Mexican smoking weed better known as ‘Mary Warner’” to school children in New Orleans. The racial history of articles in Minnesotan papers surrounding cannabis dates back to 1885 (but likely unarchived articles were published earlier) when readers in Minnesota would have learned of “The Loco Weed” which “only takes one drought to render a man insane, and all the stages of insanity, mild, violent, and finally an imbecile before death.” While articles published today about cannabis enforcement in Minnesota do not include the same racial terms, the history and origins of cannabis enforcement cannot be changed and the role of the media cannot be ignored.

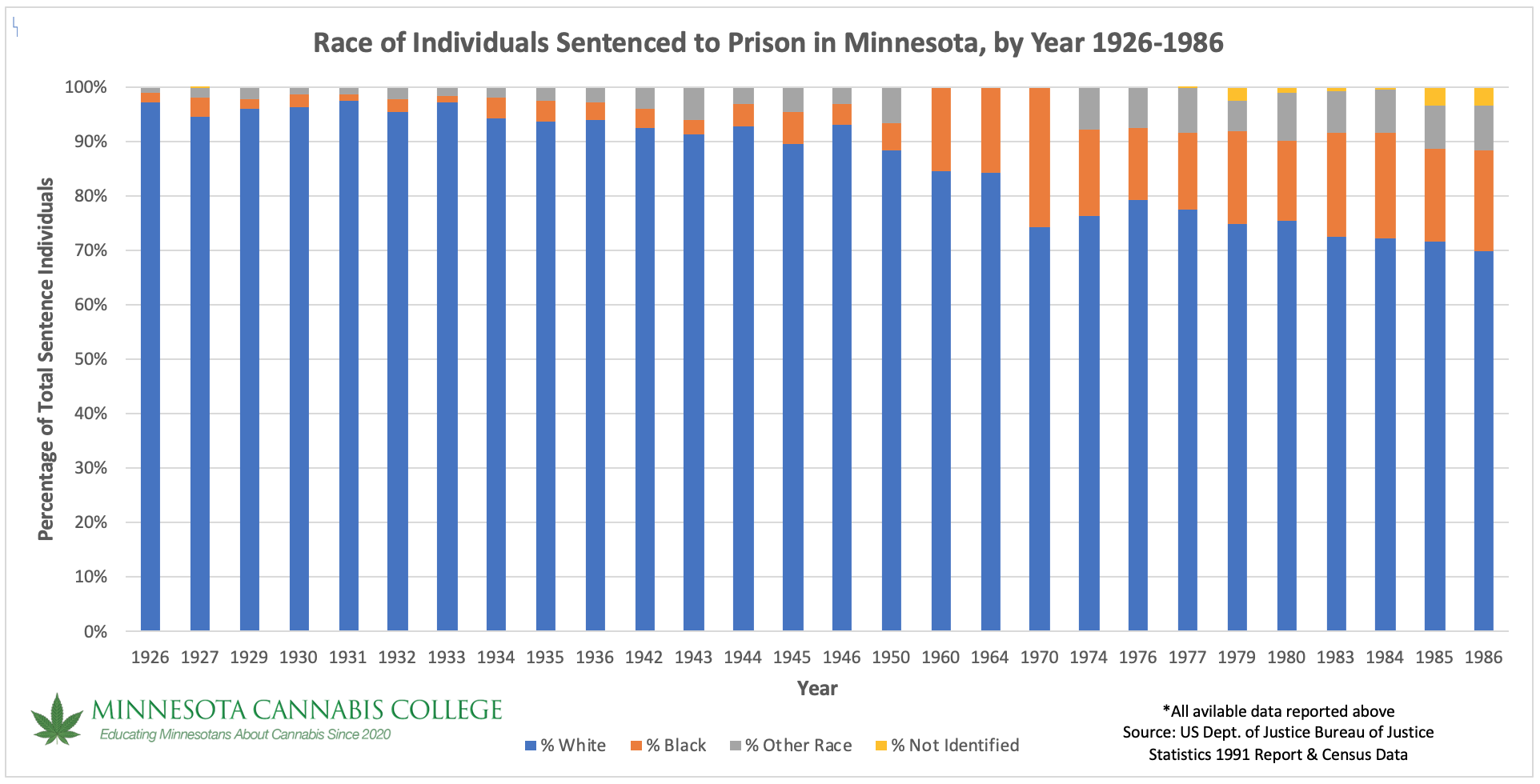

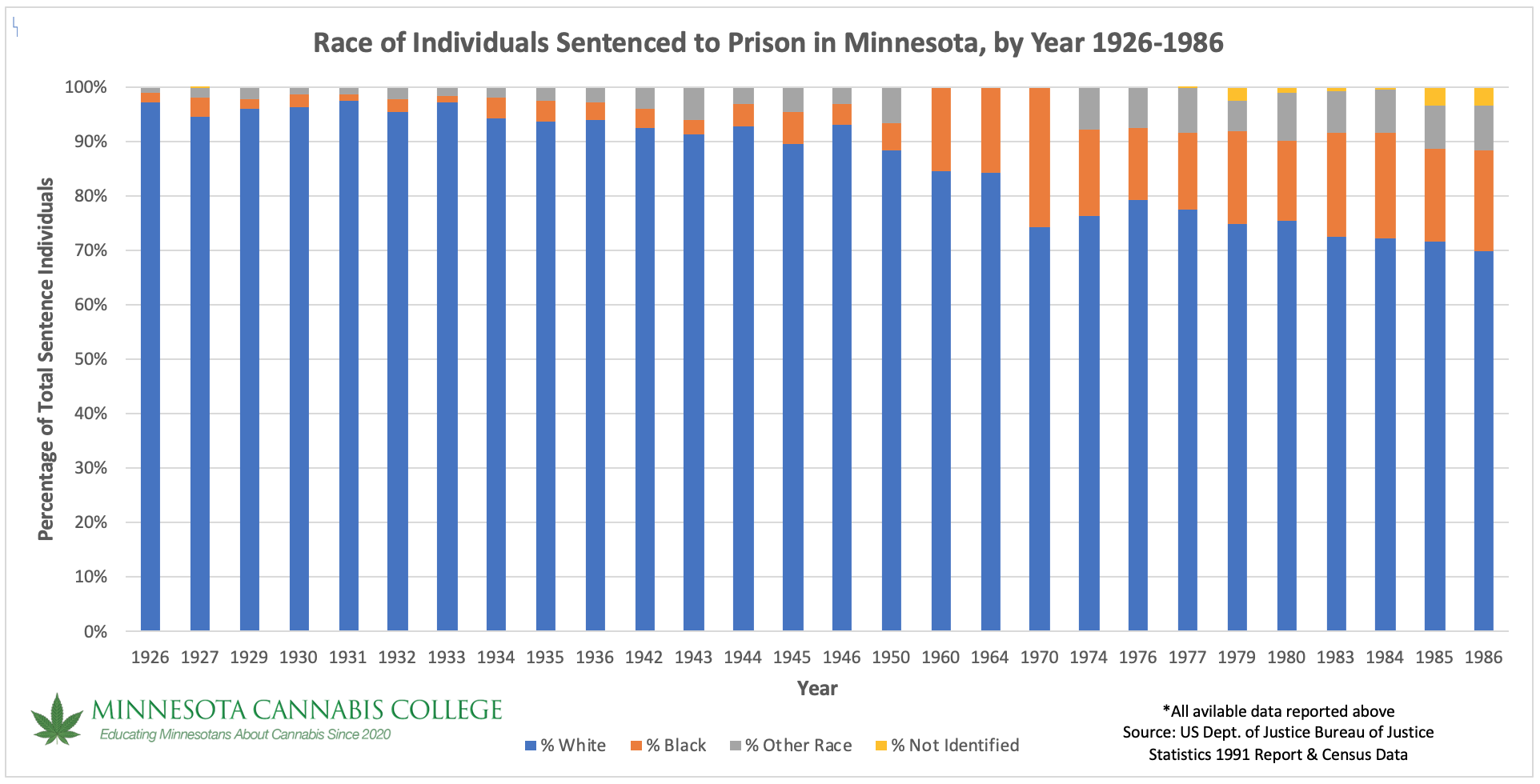

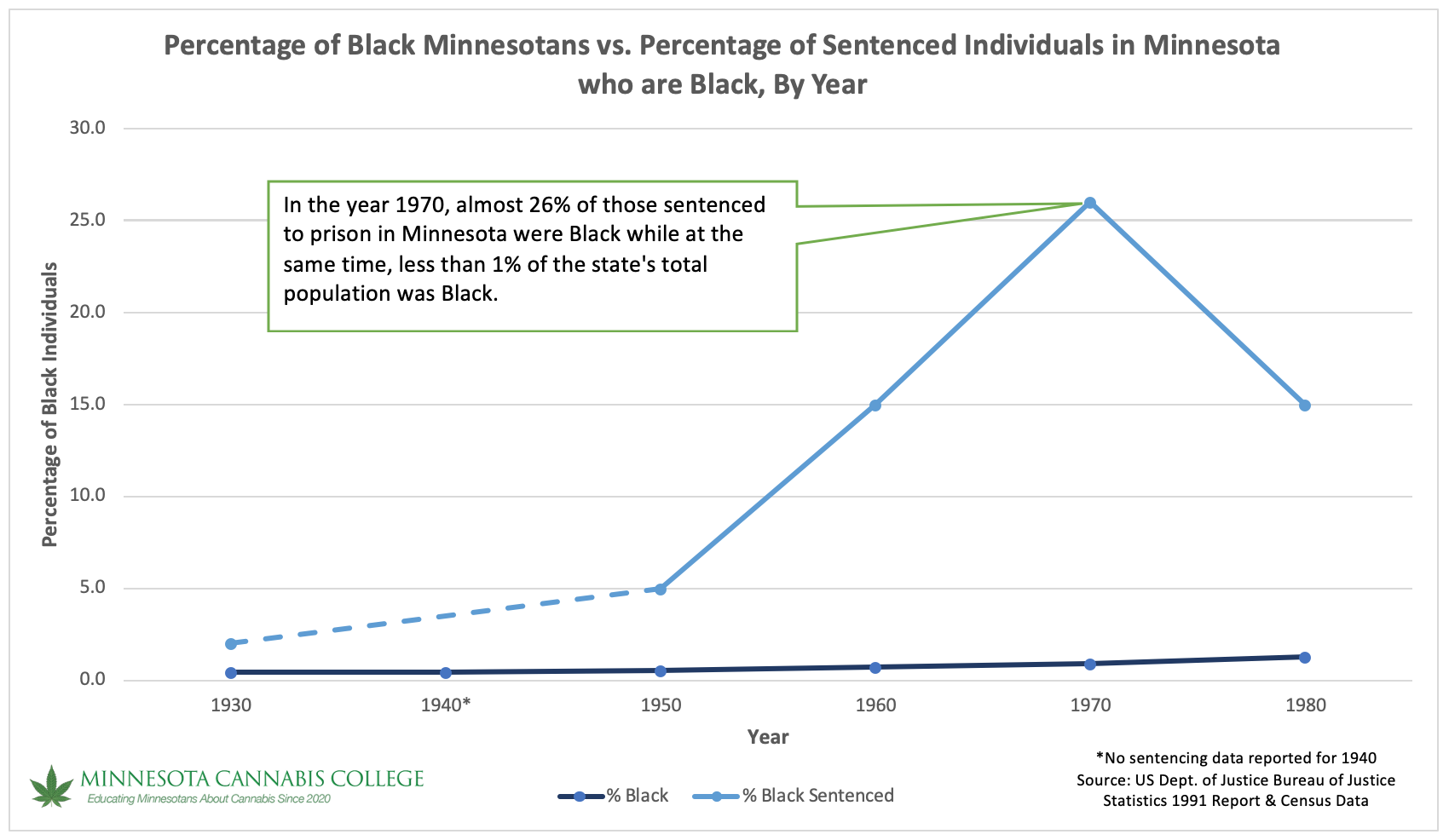

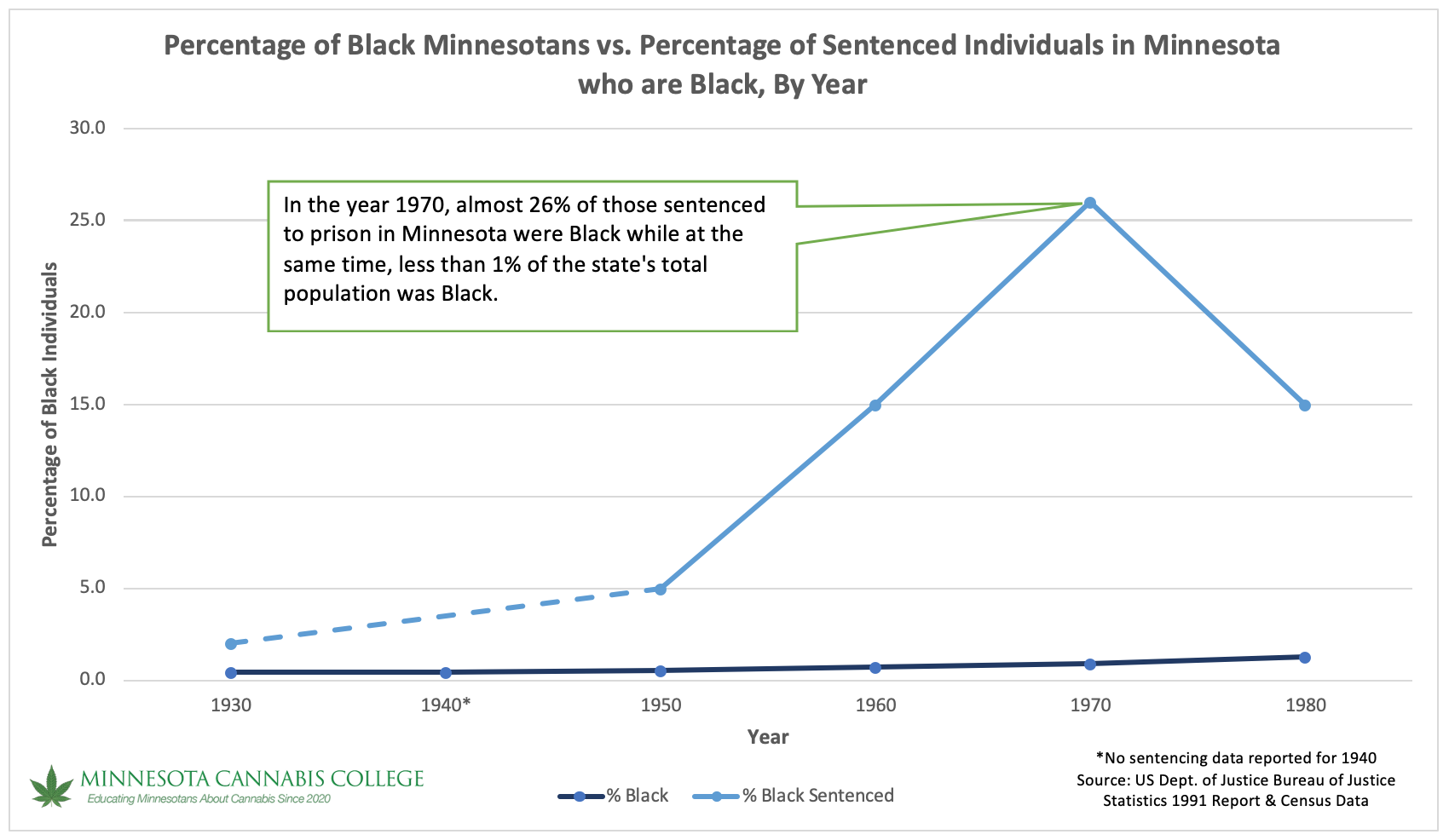

Minnesota, along with the rest of the country, began arresting individuals at an increased rate as the drug war went on. In 1935, courts in Minnesota sentenced 937 individuals to prison. Of these individuals, 6% were people of color despite the fact that less 1% of the state’s population was of color at the time. Fifty years later in 1985, Minnesota had sentenced 1,241 individuals, of which roughly 30% were people of color (despite the state’s black population only making up less than 2% of the statewide population). This increase in the percentage of inmates being of color was reflected in national sentencing records, as well.

Even today, 36.3% of prisoners in Minnesota are Black, yet only 7% of the statewide population is. Of all those behind bars, 18.3% are there because of drug-related offenses.

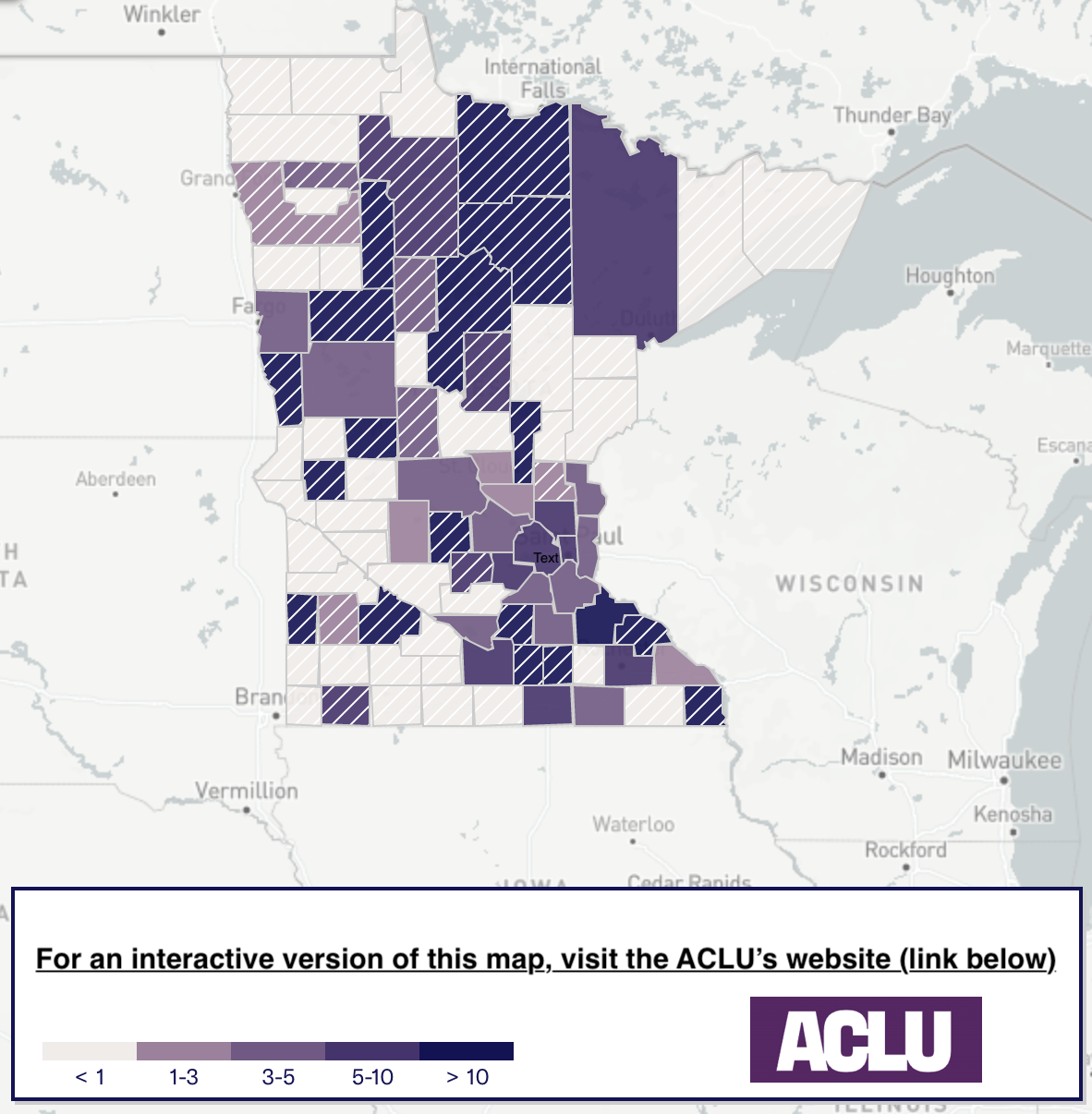

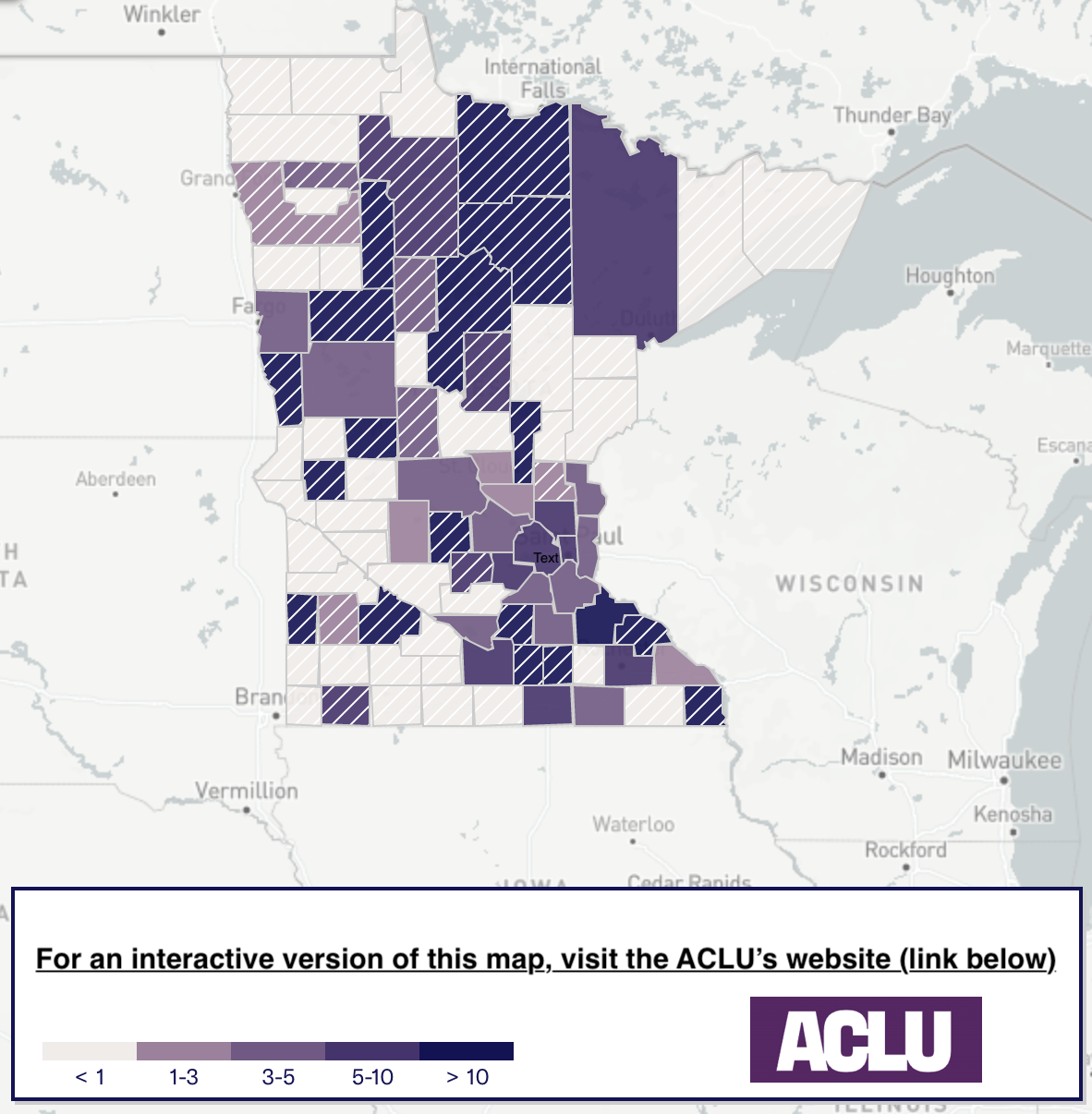

While the racially-charged statements by politicians and police surrounding cannabis may have faded, the racist effect of cannabis prohibition has not. A 2018 report from the ACLU showed that Blacks in America are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession despite similar usage rates. Minnesota is one of the worst states in the nation for this disparity, with Blacks in Minnesota being arrested at a rate of 5.4 to 1 when compared to their White counterparts. Some parts of the state are even worse than the statewide average with counties like Goodhue (11.2x), Olmsted (8.5x) and St. Louis (8.3x) reporting much larger gaps. The two largest counties, Hennepin (7x) and Ramsey (7.1x), also has disparities worse than the statewide average.

The Minneapolis Police Department ceased marijuana sting operations back in 2018 after a report concluded that 46 out of the 47 individuals arrested in the first five months of the program were black. This is in a city that is only 18% Black. The Minneapolis City Council is currently exploring alternatives to public safety in Minneapolis than the MPD.

The smell of cannabis is often used by law enforcement as a way to justify further action and use of force, sometimes with deadly results (most often for POC). Just over four years ago, an officer from the now-disbanded Falcon Heights Police Department shot and killed Philando Castile after he claimed he felt in danger for his life after smelling cannabis. The officer told investigators that “I thought if he’s, if he has the, the guts and the audacity to smoke marijuana in front of the five year old girl and risk her lungs and risk her life by giving her secondhand smoke and the front seat passenger doing the same thing then what, what care does he give about me. And, I let off the rounds and then after the rounds were off, the little girls was screaming.” After the officer was charged with manslaughter, his attorneys attempted to have the case thrown out, arguing that Castile was culpable in his own death because he was “stoned”.

Philando Castile in 2016 is just one individual in Minnesota’s history whose death at the hands of police was later justified or explained away because of cannabis use. Minnesotans such as Terence Franklin in 2013, Jamar Clark in 2015, and most recently this year George Floyd have had their murders dismissed in public by police and elected representatives because they are “druggies” and “thugs” with THC in their system. Queen Adesuyi, policy manager of national affairs at the Drug Policy Alliance, told Marijuana Moment that “Elected officials need to stop trying to weaponize stigma to justify negligence and death at the hands of the police.”

Even the term “Marijuana” has racial connotations. Before prohibition, Americans purchased cannabis-infused products from stores and ‘marijuana’ was not a word in American society. Those looking to criminalize the drug knew that American’s wouldn’t ban something they knew and had experienced, but the “loco weed” called marihuana was a different beast entirely. As explained by Business Insider, “By emphasizing the Spanish word marihuana instead of cannabis, [Harry Anslinger] created a strong association between the drug and the newly arrived Mexican immigrants who helped popularize it in the States.” It is this reason that advocates in Minnesota pushed for state law to legalize “medical cannabis” and are currently pushing for “Adult-Use Cannabis” instead of “Recreational Marijuana”. Even today, Minnesota Statutes have prohibitions on “Marijuana” while also allowing for “Medical Cannabis“.

Legislators looking to legalize adult-use cannabis are acutely aware of the racial history of the drug-war and it’s devastating effects on communities of color and low-income communities. Minnesota House Majority Leader Ryan Winkler said on a call with legalization activists back in May (just days after George Floyd’s murder at the hands of MPD officers) that racial justice was at the center of cannabis legalization. The main reason legislators wanted to reform existing cannabis laws was to “end the criminalization of people’s lives and the deep racial Injustice that are part of that system,” Rep. Winkler’s said, “Obviously, this is not going to solve a lot of problems [around racial injustice], but it does address some.”