This post is part of an ongoing exploration into a piece of legislation introduced into the Minnesota House of Representatives by Rep. Ryan Winkler, H.F. No. 4632. The full bill text can be found here.

A Tweet from Minnesota House Majority Leader Ryan Winkler explained how the upcoming November election would impact the state’s cannabis community. “What’s at stake for MN in this year’s #mnleg election,” Rep. Winkler asked, “Legalization & expungement.” With this being National Expungement Week, we wanted to ask: what does Winkler’s bill actually say will happen in regards to the expungement of cannabis convictions? Some other states, such as New York, have created processes so the charges are like they “never happened”, but what will happen in Minnesota?

The cannabis legalization bill introduced by Winkler and other legislators at the tail end of the previous session, House File 4632, created two categories of expungement: automatic and panel decision. The latter of which would be reviewed by the Cannabis Expungement Board, a five-member executive committee that would be made up of the state’s Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the state’s Attorney General, along with a public defender, a State Commissioner, and a public member, all appointed by the Governor.

Automatic expungement would only be available to those convicted of possession crimes. For those in this category, the state (through the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension) would identify eligible individuals and work to expunge the records themselves. This means that unlike some states where individuals need to take action, Minnesota will automatically take action without needing the individual to complete a form or consent. In fact, almost all expungements in Minnesota require a court hearing, but the bill (as it’s currently written) allows for the court to issue an Order of Expungement without requiring a hearing, meaning we can hopefully expect a speedy and efficient process for expunging applicable records.

Outside of this bill, an order for expungement does not exclude the records from certain uses by the state of Minnesota, such as when you apply for certain professional licenses and when applying for a gun license. This means that if an individual gets their records expunged, they are still accessible to the state agencies that grant teacher and peace officer licenses (two separate state agencies, just in case that was unclear). While that doesn’t bar you from seeking to obtain a teaching license, it does make it more difficult and the process more cumbersome. HF 4632 explicitly states that “An order issued under this section shall be directed to the commissioner of human services, the Professional Educator Licensing and Standards Board, or the licensing division of the Department of Education.”

This legislation does not allow individuals with expunged cannabis records to become peace officers, meaning that even if you have a cannabis possession conviction from the 1970s, you are still banned from becoming a law enforcement officer in Minnesota. That’s currently the law, and as written, HF 4632 would not change that.

Aside from the automatic process, there is also a panel approval process. Any individual convicted of a felony-level drug possession crime in Minnesota related to cannabis will need to apply for expungement; it is not automatic. This means that those caught possessing ten kilograms or more of cannabis (or any amount of concentrate) will need to apply and appear before the Cannabis Expungement Board. This board will have the ability to expunge, resentence, or restore various civil rights (such as the right to possess firearms) for all possession crimes not covered by the automatic process.

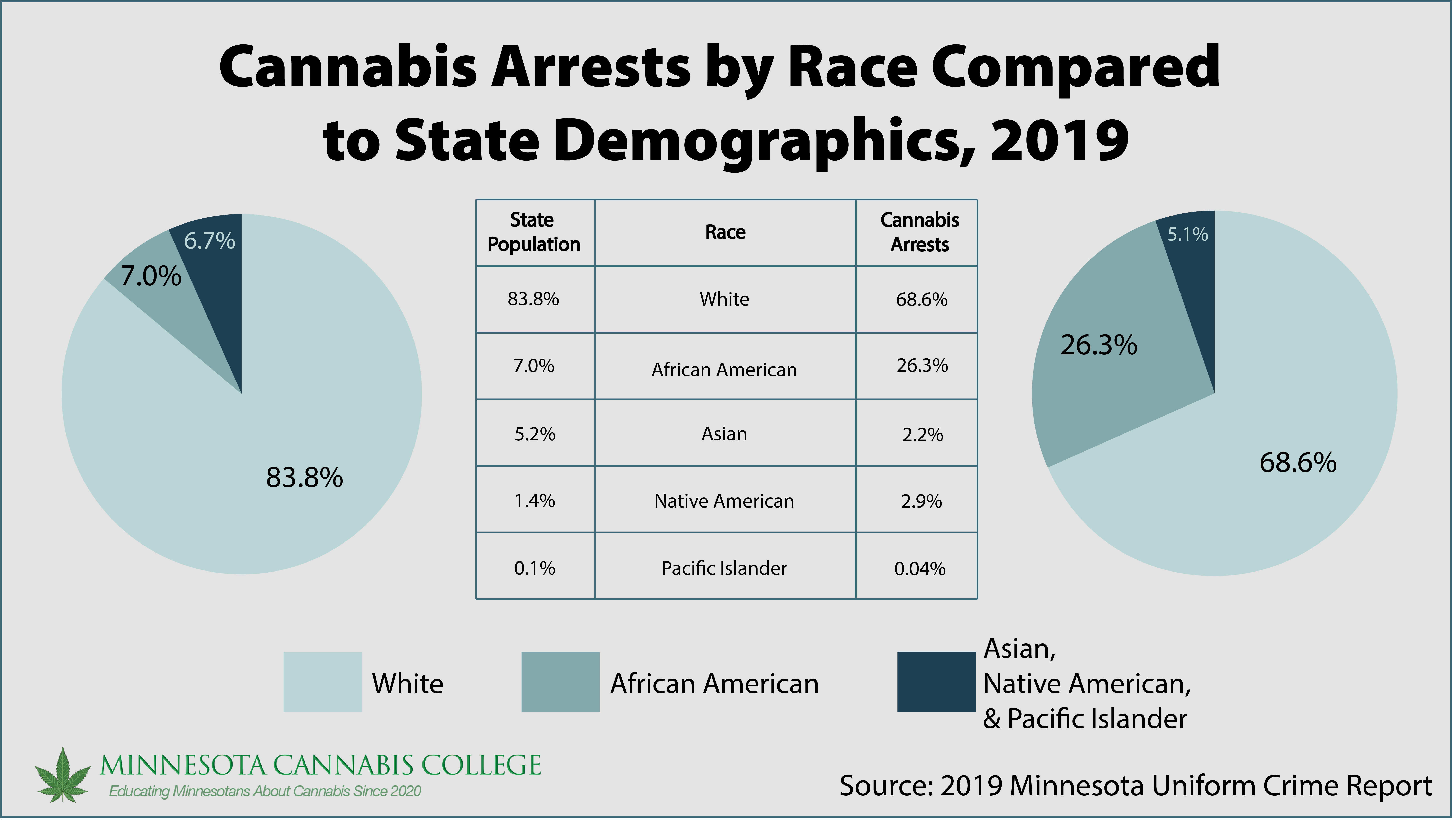

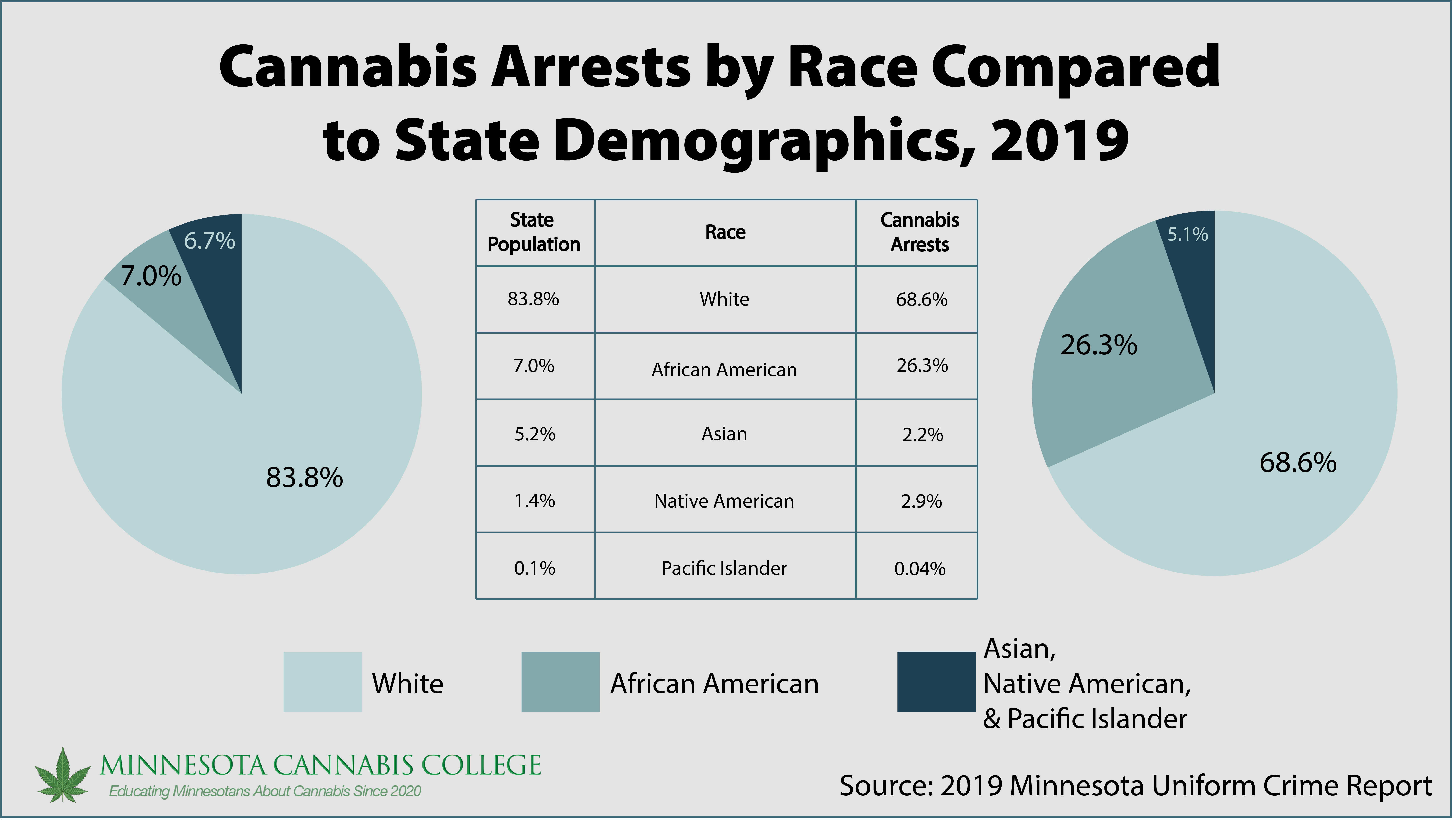

Individuals with convictions for sale of cannabis, however, regardless of the amount, will be unable to seek expungement for those offenses. This is not a small number: in 2019 alone, over 1,300 individuals were arrested for selling cannabis, according to the Minnesota BCA. This has the most significant effects on Minnesotans of color, who make up a disproportionate amount of cannabis arrests in the state. In 2019, for example, over 26% of those arrested for cannabis-related offenses were Black, despite only 7% of the state being Black (according to data from the US Census).

Jon Geffen, Director of the Reentry Clinic at Mitchel Hamline, said that expungement provisions in this legislation were a big improvement over prior bills to legalize cannabis. “I like this version a lot more,” said Geffen, “but I still think there are issues.”

Some of the issues that Geffen identified would need to be ironed out as the bill moves through committees, such as who actually sends documentation from the BCA and who actually receives it at Judiciary. Another example of an issue that Geffen gave was in the case of disputes or objections. The current process mandates a hearing, which allows other state agencies to be part of the process. That is not included in the automatic expungement process, so state agencies would not be able to impact the process for those applying for automatic expungement. In essence, state agencies cannot object to automatic expungements. For some, this may be an issue for the bill, others an advantage.

One issue that was identified by Tom Gallagher, an attorney and former Chair of Minnesota NORML Board, was the difference between vacating and expunging charges. “The term “expungement,” standing alone, is now tainted, ambiguous,” Gallagher wrote, “due to Minnesota usage.” He instead advocated for vacating and expunging prior cannabis convictions so that individuals are fully restored of their civil rights. While most rights are restored during an expungement, not all are. Gallagher sees this as a fatal flaw in the process, whereas Geffen disagrees. “I want people to get jobs, I want people to live whole lives; if you can’t go shooting, I’m not as concerned,” Geffen said, noting that processes already exist for those looking to restore certain rights stripped when convicted of drug-related offenses.

Regardless of where you stand, the issue of unclear language is not new in the Minnesota Judicial system where individuals regularly have contradictions in the court’s decisions. For example, an individual who is pardoned by the Governor does not have their criminal record removed from public access, but the conviction is technically no longer on your record. This means that when someone would search for their name and find the outcomes of their case, it will say “pardoned” instead of “convicted”. Even with that note, it still shows the charge and prior court action. If that individual applied for a job, indicating on the application that they had no criminal history (which is technically correct post-pardon) and consented to a background check, their employer would find that pardon (along with the conviction). “The ridiculous part of that” Geffen explained, “is that you don’t ever have to admit that you were pardoned… but everyone can still see the record.”

Judge Gordon Shumaker summarized the issue well when writing in a Court of Appeals decision: “On the one hand, he can deny his prior conviction as the pardon and the laws entitle him to do, but anyone who checks his record will likely conclude that he lied. Now he is both a criminal and a currently dishonest person.”

As Winkler’s legislation gets debated and amended this upcoming session, the bill’s text related to expungement might (and likely will) change. Marcus Harcus, Executive Director of the Campaign for Full Legalization, believes that more needs to be done, calling the current proposal “insufficient”. Harcus believes that all nonviolent cannabis-related should be eligible for expungement (instead of just possession charges) and that many more convictions than currently proposed need to be automatically processed.

“There’s a lot of people that cannot [go through the expungement process] on their own,” Harcus said. “If the people with these records have to be informed to know that there are opportunities to get it expunged, and then they have to go through the process of petitioning to get these expungements, a lot of people are going to fall through the cracks,” Harcus explained, “A lot of people who are low-income or not-college graduates are highly transient… even if you send out notifications, a lot of these people are not going to be at the same place they were last year.”

Harcus also believes that the authors of the legislation need to revisit the idea of allowing pardons for non-violent cannabis felonies. Have you ever made pot brownies and sold one to a friend? That’s a felony. Or do you live in public housing and sold an eighth to a friend when they came over? That’s also a felony. Or are you a dumb high school senior who brought some weed to school to sell to a classmate? Felony. All of these individuals would be ineligible for expungement under the proposed legalization bill. “We’ve got to do better,” Harcus explained, “cannabis never should have been prohibited to begin with and these people need their records clean.” In 2018 alone, over 700 people were convicted for felony-level cannabis offenses, and their records will not be clean while at the same time, others are making a living and paying taxes to the state based on the same activity. “Most states have focused on misdemeanors, but they’re not touching the felonies. But there’s a lot of people with felonies.”

“Oh, there’s not that many people with felonies, only a few thousand,” Harcus said in a sarcastic tone. “Only a few thousand lives.”

More information about House File 4632 can be found below:

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I’ve found something which helped me. Appreciate it!