From the early days of cannabis prohibition in Minnesota, racism has consistently served as a driving force for the increase in enforcement funding and the severity of punishments imposed on those apprehended. Although politicians today may insist that their support for drug enforcement is not inherently racist, it does bolster the continuation of policies that were originally conceived to oppress and criminalize people of color, as well as individuals living in poverty. John Ehrlichman, who was the Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs under Nixon, infamously asserted that the initial reason behind drug prohibition was to criminalize and incarcerate “hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin.” The purpose was, and continues to be, to disrupt communities and detain those labeled as “undesirable” by the political system.

The original legislation enforcing cannabis prohibition in Minnesota was instituted in 1935, a mere two years before the national criminalization. Chapter 321 forbade the possession, production, and sale of “Cannabin”, and penalized violators with a $1,000 fine and up to a one-year prison sentence (or longer for subsequent offenses). By the 1940s, with the film “Reefer Madness” screening in Minnesota theaters, fields of cannabis (including the low-THC plant commonly referred to as Hemp) were being eradicated by the acre.

Although the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery, the early enforcement of cannabis prohibition carried on the tradition by sentencing those arrested for possession in Minneapolis to 90 days of forced labor in a workhouse (which was deemed liberal at the time). The Minneapolis Tribune reported on June 17, 1931, that the new city ordinance prohibited “marijuana, a Mexican drug.” Just a decade earlier, readers would have learned of a raid on providers distributing “a Mexican smoking weed better known as ‘Mary Warner'” to school children in New Orleans. The racial history embedded in Minnesotan publications regarding cannabis can be traced back to 1885 (and likely earlier, though unarchived articles may have been published) when readers in Minnesota would have learned of “The Loco Weed” that “only takes one draught to render a man insane, and all the stages of insanity, mild, violent, and finally imbecility before death.” While contemporary articles on cannabis enforcement in Minnesota do not use the same racial terminology, the history and origins of cannabis enforcement remain unchanged and the role of the media cannot be overlooked.

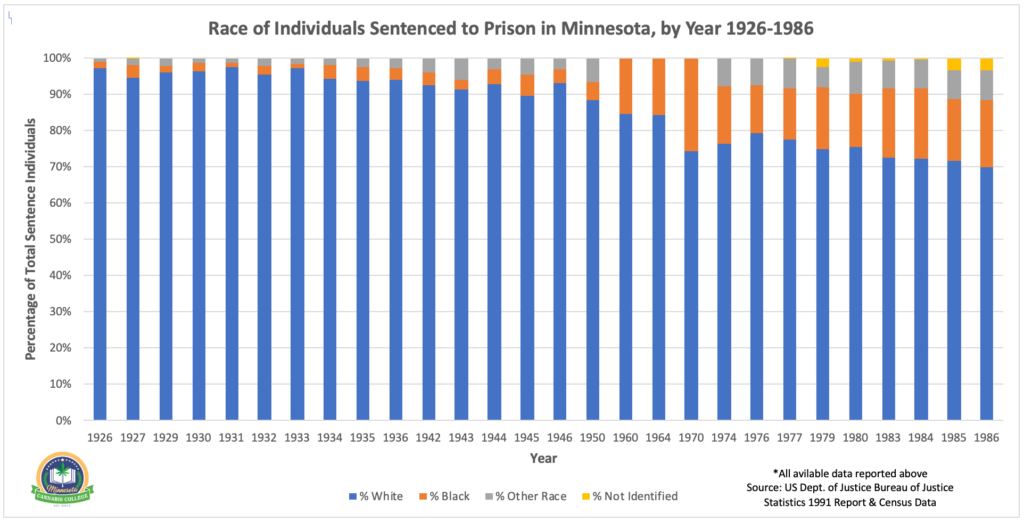

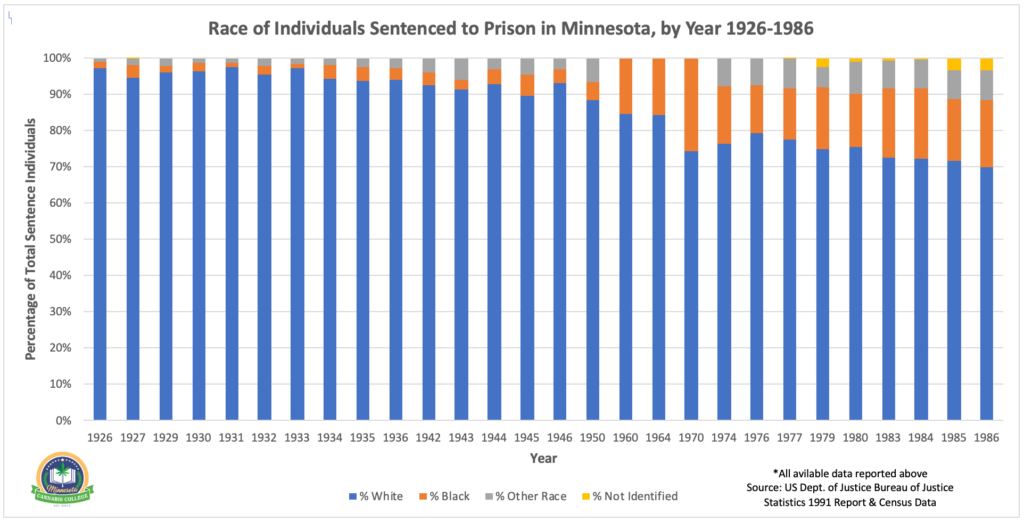

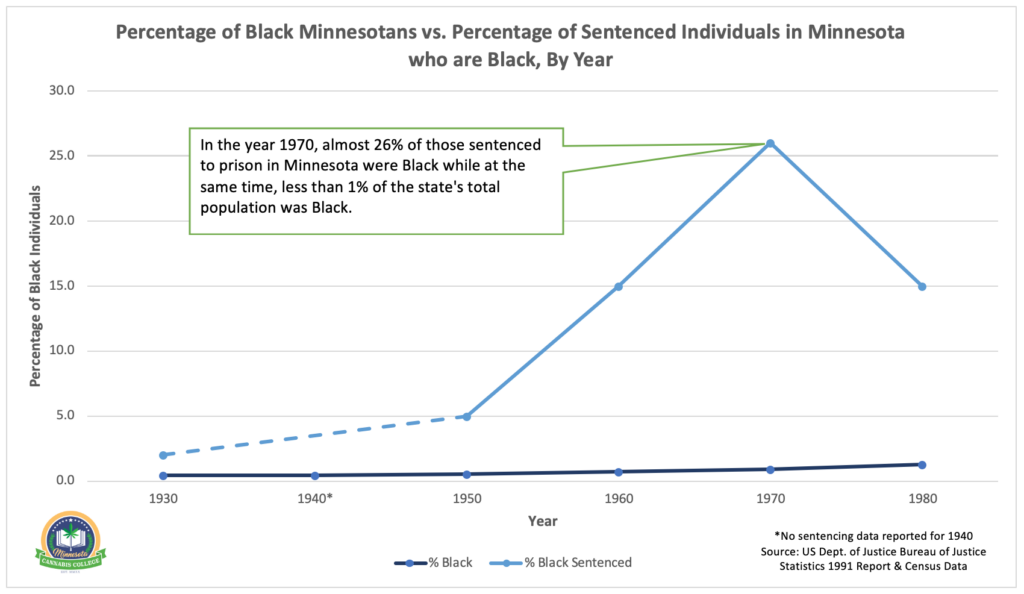

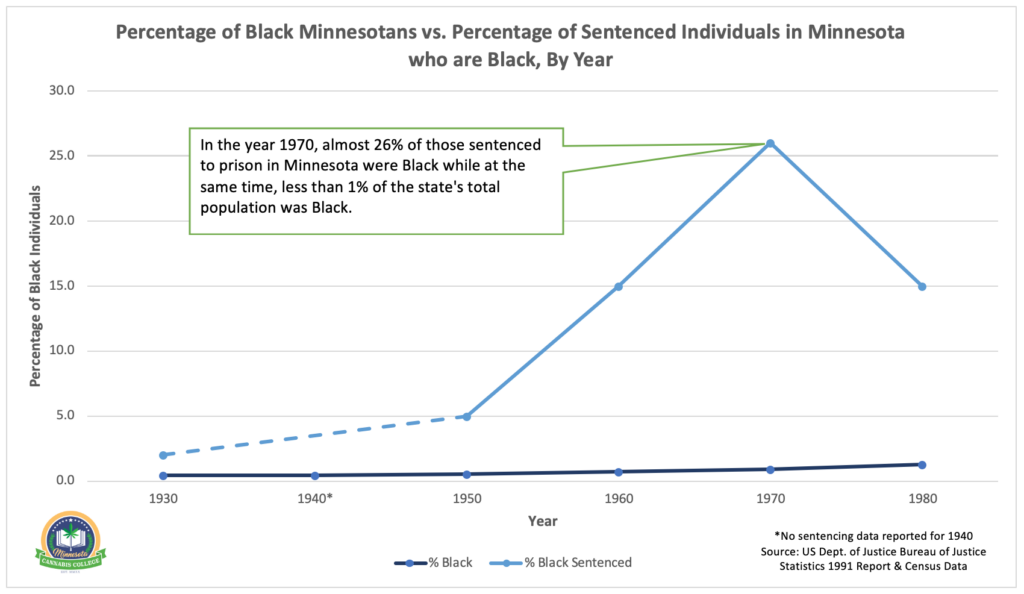

As the war on drugs continued, Minnesota, along with the rest of the country, saw a surge in the arrest rate. In 1935, Minnesota courts sentenced 937 individuals to prison. Of these individuals, 6% were people of color, even though less than 1% of the state’s population was of color at that time. Fifty years later in 1985, Minnesota had sentenced 1,241 individuals, roughly 30% of whom were people of color (despite the state’s Black population making up less than 2% of the statewide population). This increase in the percentage of inmates being of color was reflected in national sentencing records, as well.

Today, 36.3% of prisoners in Minnesota are Black, despite making up only 7% of the statewide population. Of all those incarcerated, 18.3% are there because of drug-related offenses.

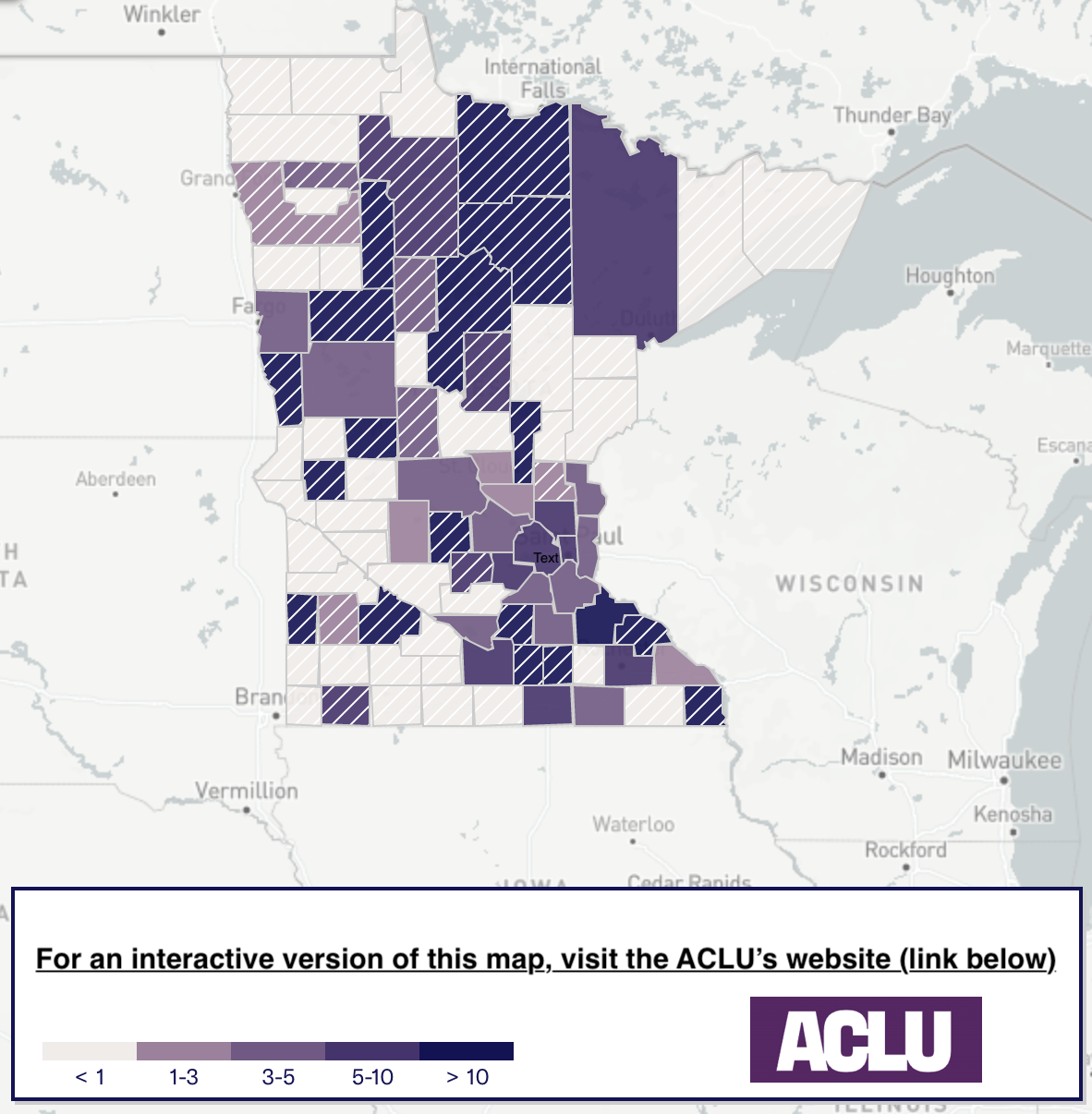

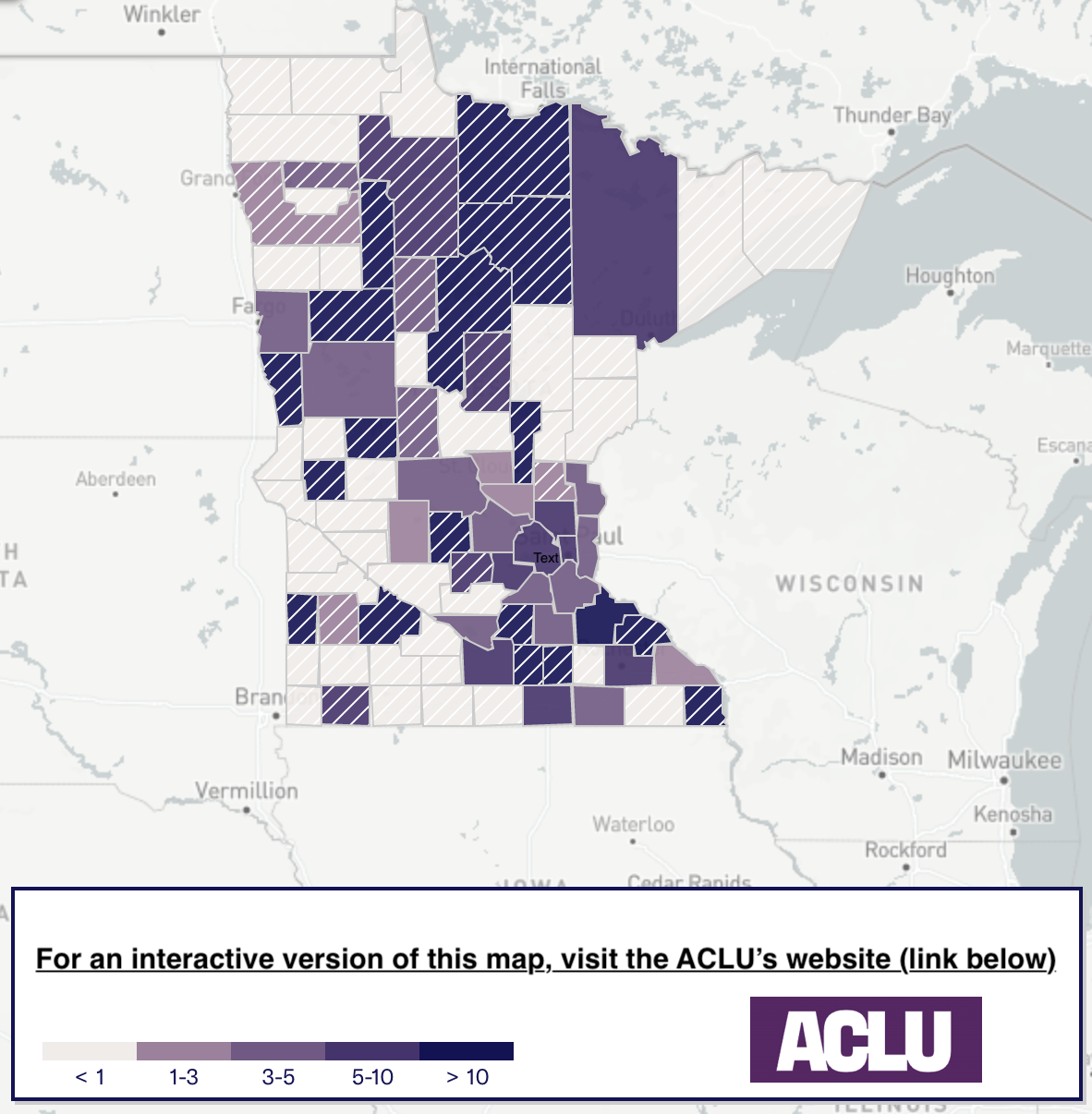

While the overtly racially-charged rhetoric surrounding cannabis may be less prevalent, the racially discriminatory impact of cannabis prohibition remains significant. A 2018 report from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) revealed that despite comparable rates of cannabis use, Black individuals in America are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession. Minnesota ranks among the states with the highest disparity in this respect, with Black Minnesotans experiencing arrests at a ratio of 5.4 to 1 compared to their White counterparts. Some regions in the state exhibit even higher disparities, with counties like Goodhue (11.2x), Olmsted (8.5x), and St. Louis (8.3x) reporting larger racial gaps. The two largest counties, Hennepin (7x) and Ramsey (7.1x), also report disparities exceeding the statewide average.

The Minneapolis Police Department discontinued marijuana sting operations in 2018 following a report revealing that out of 47 individuals arrested in the program’s initial five months, 46 were Black in a city with an 18% Black population. The MPD is now prohibited from using the odor of cannabis as a pretext to search vehicles, following multiple reports indicating racially-biased enforcement of this practice.

The odor of cannabis is often utilized by law enforcement to justify escalation and, at times, the use of lethal force—disproportionately affecting people of color. Over four years ago, a Falcon Heights Police Department officer fatally shot Philando Castile, asserting that he felt endangered after detecting the smell of cannabis. The officer’s defense and subsequent manslaughter charges initiated debates about cannabis-related stigma and culpability in deadly incidents.

The officer told investigators that “I thought if he’s, if he has the, the guts and the audacity to smoke marijuana in front of the five-year-old girl and risk her lungs and risk her life by giving her secondhand smoke and the front seat passenger doing the same thing then what, what care does he give about me. And, I let off the rounds and then after the rounds were off, the little girls was screaming.” After the officer was charged with manslaughter, his attorneys attempted to have the case thrown out, arguing that Castile was culpable in his own death because he was “stoned”.

Indeed, Philando Castile’s case in 2016 is one among several instances in Minnesota’s history where law enforcement’s lethal use of force was later justified or dismissed due to the victim’s alleged cannabis use. Instances like those of Terence Franklin in 2013, Jamar Clark in 2015, and George Floyd in 2020 have seen their tragedies downplayed by some police and elected officials, who label them as “druggies” and “thugs” due to THC presence in their systems. Queen Adesuyi, policy manager of national affairs at the Drug Policy Alliance, asserted that “elected officials need to stop trying to weaponize stigma to justify negligence and death at the hands of the police.”

Furthermore, the term “marijuana” itself carries racial undertones. Prior to prohibition, Americans were accustomed to purchasing cannabis-infused products, and ‘marijuana’ was not part of the American lexicon. However, those advocating for the drug’s criminalization understood the public’s reluctance to ban a familiar substance, hence they introduced the foreign-sounding term ‘marihuana’ to associate the drug with newly-arrived Mexican immigrants who were popularizing its use in the U.S. This tactical language shift underscores the potency of words in shaping public perception and policy. Consequently, many reform organizations are now preferring the use of ‘cannabis’ over ‘marijuana’.

While we move into the next chapter of cannabis policies impacting communities of color, it’s important for us to not forget the history of our state. Lawmakers who worked to bring about cannabis legalization talked of the racial history of the drug war and its devastating effects on communities of color and low-income communities.

The main author of the cannabis legalization bill in the Senate, Senator Lindsey Port, stated that the prohibition on cannabis has “done immeasurable harm to our people, disproportionately to people of color.” Representative Zach Stephenson echoed the sentiment, saying that with legalization, the state will “begin the process of undoing the cost of prohibition on communities all across the state by beginning expungements.” It’s clear that lawmakers understand the impact of race on cannabis prohibition, but questions remain as to if the next chapter will begin to repair those harms.

Who will be given preference when issuing cannabis business licenses?

What communities will see investment from public and private funding?

Who will receive relief from the Cannabis Expungement Board?

Will the legalization of cannabis in Minnesota mark the beginning of a genuine effort to rectify the damage caused by the War on Drugs? Only time can tell.

—

Want to learn more about the importance of Social Equity in Legal Cannabis? Watch our panel on the topic today.